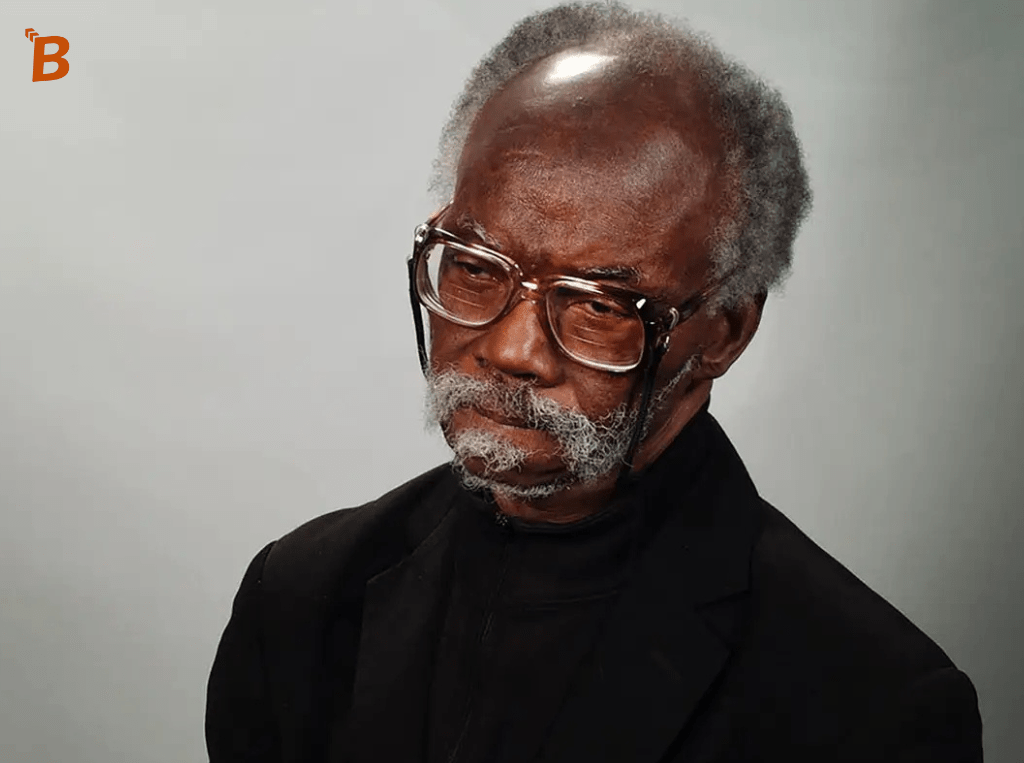

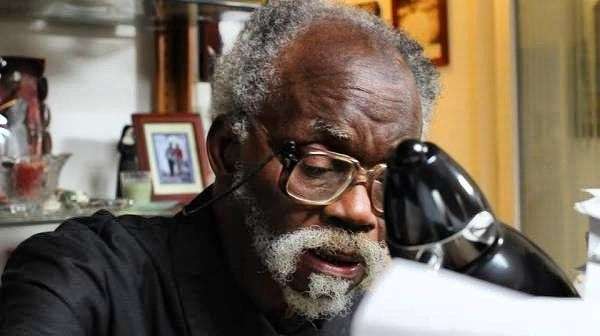

Valentin-Yves Mudimbe was not the kind of intellectual who chased headlines. He didn’t lead protests or deliver fiery speeches. Instead, he waged his revolution with relentless, deeply researched, and powerfully disruptive ideas.

On April 21, 2025, Africa lost one of its most original minds – Mudimbe. He passed at the age of 83 in the United States, where he had lived for decades.

Valentin-Yves Mudimbe was a Congolese philosopher, linguist, novelist, and scholar whose work reshaped African studies and postcolonial thought.

His writing asked unsettling questions; such as – who gets to define Africa? What knowledge counts as valid? And how do we escape the intellectual cages left behind by colonial rule?

Early Life

Born in 1941 in Jadotville, now Likasi, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mudimbe’s intellectual journey began in a Benedictine monastery.

The strict routines of religious life and classical education left a lasting imprint, but so did the questions they raised. Faith gave him language; philosophy taught him how to interrogate it.

Later, he studied in Belgium at the Catholic University of Louvain, gaining exposure to European intellectual traditions.

But even as he absorbed their frameworks, he kept a critical eye. He would eventually come to challenge the very systems that had trained him.

DON’T MISS THIS: The Cross and the Chains: the Church of England’s evil role in African slavery

Exile and engagement

In 1970, Valentin-Yves Mudimbe returned to Congo, eager to contribute to the intellectual life of the newly independent nation.

He began teaching at the National University of Zaïre. However, the idealism of independence was quickly eroded by authoritarianism.

Under President Mobutu Sese Seko, the regime pushed a state-sponsored notion of “authenticity,” weaponised to silence dissent voices.

Mudimbe saw through the illusion. In 1979, faced with a stifling political atmosphere, he left the country. But exile didn’t sever his ties to Africa.

From classrooms in Stanford and Duke University, he remained deeply invested in the continent’s cultural and philosophical future. He used distance not to disconnect, but to observe more clearly, and critique more sharply.

The invention of Africa

His most celebrated and widely read work, The Invention of Africa (1988), is still shaking the foundations of African studies.

In it, Valentin-Yves Mudimbe introduced the idea of the “colonial library“, a metaphor for the vast body of texts, ideas, and disciplines that defined Africa from the outside.

Missionaries, anthropologists, administrators, many had written about Africa, but rarely with it or from it.

He exposed how Africa had been cast not as a flawed or misunderstood civilisation, but as a blank slate, a void.

This framing justified the colonial project. Africa was seen as something to be filled, saved, explained. Mudimbe argued that even well-meaning critiques of colonialism often used the same intellectual tools that colonialism itself created.

He asked, how can we produce knowledge that doesn’t repeat the very frameworks we seek to dismantle?

Building afresh

Yet Valentin-Yves Mudimbe wasn’t interested in merely tearing things down. He believed in building something better.

For him, decolonising knowledge wasn’t about returning to a mythical pre-colonial past or creating new dogmas in the name of cultural pride. It meant crafting fresh intellectual systems – open, plural, and self-aware.

He warned against essentialism, the temptation to create new rigid identities under the guise of reclaiming culture.

His method was disciplined and rigorous – analyse the discourse, question the categories, dismantle the false assumptions.

For Mudimbe, freedom begins in the mind.

Fiction as philosophy

His ideas lived in novels like Between Tides, Before the Birth of the Moon, and Shaba Deux. Mudimbe explored identity, exile, and memory through characters navigating the chaos of postcolonial life. His fiction was not separate from his philosophy, it was an extension of it.

Language in his novels was a site of struggle. His characters wrestled with history, faith, and fractured identities in stories that mirrored the complexity of African experience. He refused clichés. He rejected simplifications. Every sentence was a challenge to see differently.

A legacy for the future

Mudimbe’s influence runs through the work of leading contemporary African thinkers like Achille Mbembe, Souleymane Bachir Diagne, and Felwine Sarr.

He laid the intellectual groundwork for a new kind of African scholarship – one that doesn’t just respond to the West but reimagines what it means to know, to question, to be.

In a world where conversations about decolonisation are growing louder, Mudimbe’s legacy is more relevant than ever. He reminds us that true liberation is not only political or cultural. It is intellectual. It is about how we name the world and our place in it.

Valentin-Yves Mudimbe did not ask us to agree with him. He asked us to think harder, to ask better questions, to dismantle easy answers.

He showed that identity is not a fixed truth but a field of possibility, and that Africa’s story is still being written, but only if we dare to write it ourselves.