This is the story of African slavery, the role played by the Church of England, and how it twisted faith into a tool of oppression.

Between the 15th and 19th centuries, an estimated 12.5 million Africans were violently uprooted from their homelands and shipped across the Atlantic Ocean in what remains one of the greatest crimes against humanity – the transatlantic slave trade.

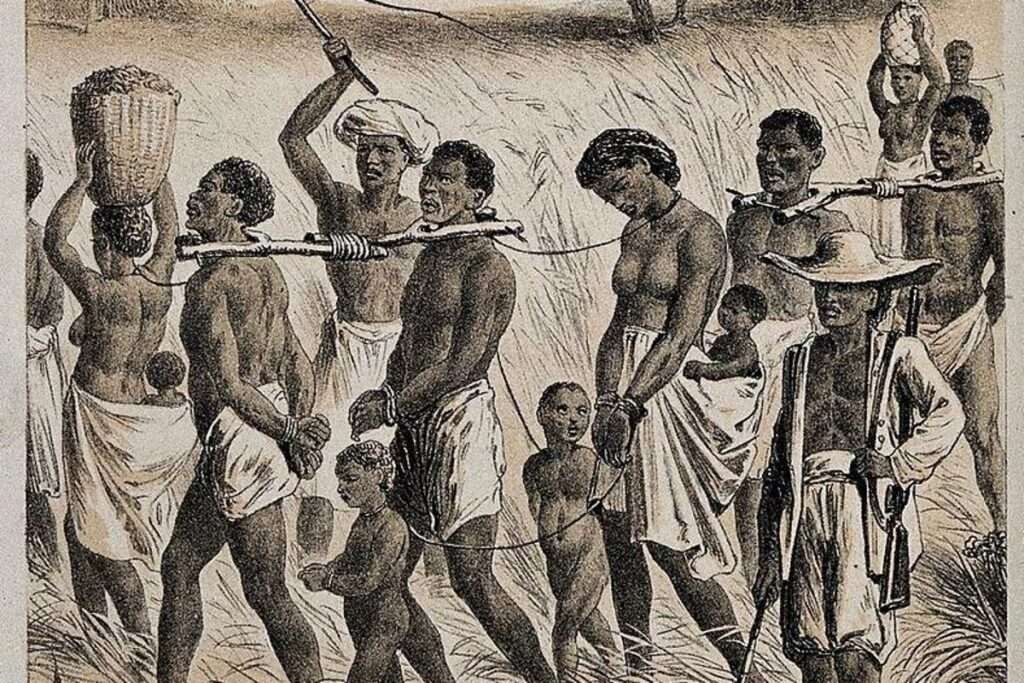

These were not just numbers. They were mothers, warriors, healers, blacksmiths, kings and queens – people with names, dreams, and histories, snatched by force and sold like livestock.

About 2 million died in the voyage alone. They were tossed into the ocean like waste.

The rest were sent to work on plantations in the Caribbean, Brazil, and the American South. Their labour built Western empires. Their suffering lined European pockets.

Once captured through coastal raids or local wars, often fueled by European demand, enslaved Africans were crammed into ships and sent primarily to:

- The Caribbean (about 48%) – islands like Barbados, Jamaica, and Saint-Domingue (now Haiti)

- Brazil (around 40%) – more enslaved Africans were sent here than to any other single country

- North America (approximately 5%) – particularly the southern United States.

- Spanish America and other European colonies

Bibles in one hand, chains in the other

But there was another export that came with the traders and soldiers – Christian missionaries, many of whom worked hand-in-hand with colonial authorities, preaching obedience while standing on stolen land.

Religious institutions falsely sanctified the slave trade. Among them, the Church of England stood tall.

In 1710, the Church – through its missionary arm, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) – was gifted two sugar plantations in Barbados by a wealthy slave-owning Anglican named Christopher Codrington.

These estates, worked by enslaved Africans, generated massive profits that were sent back to England to fund missionary schools and build churches, and they inherited two sugar plantations in Barbados.

Sir Hilary Beckles, a leading historian, explains:

“Caribbean people continue to suffer economic deprivation and poor health as a direct result of the injustices of slavery.”

The Church didn’t just benefit economically. It branded its initials (S.P.G.) on the chests of the enslaved. Children as young as six were forced into labour.

Women were exploited to breed more slaves. Yet, Sunday services were held on the plantations. Prayers were offered. Hymns were sung. while whips cracked on Mondays.

“Religion is NOT God. It is the social engineering of spirituality and faith – man’s attempt to capture God.”

Eyewitness to horror – Olaudah Equiano

One of the most powerful testimonies about the horrors of the slave trade comes from Olaudah Equiano, a former enslaved African who bought his freedom and became a leading abolitionist.

He wrote in his autobiography:

“The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable.” – Olaudah Equiano, 1789

This description of the Middle Passage – the sea journey that claimed millions – captures the inhumanity suffered by Equiano and his fellow captives.

West Africa and the weaponised Gospel

In Nigeria, Ghana, and Sierra Leone, the arrival of Christianity was framed as “civilisation.” But no less damaging. Only that this time, it was psychological colonisation.

By the 1800s, slavery had been abolished in Britain, but the racial superiority mindset remained.

The Church Missionary Society (CMS), under Anglican authority, began “civilising” missions.

They built churches and schools, but also undermined African spirituality, discouraged traditional customs, and imposed Western cultural norms under the guise of salvation.

Even when Africans embraced Christianity and rose in its ranks, they were systematically marginalised. They were reminded they were never truly equal to the white missionaries.

Samuel Ajayi Crowther, a Yoruba man once enslaved and later freed, became the first African bishop in the Anglican Church.

He translated the Bible into Yoruba, opened schools, and trained local clergy.

Yet he was constantly undermined by white missionaries who didn’t believe Africans were “ready” to lead.

But according to scholar Andrew F. Walls, Crowther’s position was deliberately weakened:

“Crowther’s position was more symbolic than functional, as his power to appoint clergy and make decisions was limited.”

Crowther’s treatment revealed the Church’s deep racial hierarchies, even within its own fold.

The reckoning begins

In 2023, after years of pressure and documentation, the Church of England formally acknowledged its role in the slave trade.

It pledged £100 million toward racial justice and reparative initiatives over a 9-year period.

The Church confessed:

“We can and will recognise and acknowledge the horror and shame of the Church’s role in historic transatlantic chattel slavery.” – Church of England statement, 2023, quoted by Al Jazeera.

This admission followed mounting evidence, spanning historical records, academic research, and public outcry that revealed how Christian institutions not only benefited from slavery but also blessed it theologically and morally.

Why this truth still matters

Historian Marcus Rediker, who studied the slave trade for decades, puts it plainly:

“The slave ships are ghost ships still sailing around the edges of our modern consciousness. Their legacy in the present is discrimination, deep poverty, structural inequality, and premature death.”

If you are a young African, whether in Accra, Lagos, London, or Atlanta, know that the systems of injustice, racial inequality, and cultural dislocation we experience today were shaped in part by religious institutions that claimed to be moral authorities.

To heal, we must confront the whole truth. Not to discard faith, but to disentangle it from the colonial ideologies and power structures that once used it to enslave us.

We must embrace faith and spirituality but distance ourselves far from religion, which is not God. It is the social engineering of spirituality and faith. IT IS NOT GOD!